St. Petersburg where she had survived my father's death by ten years. We both had the shrimp.

Less than a month later she fell and broke her hip. While she was recovering after an operation to give her a new hip, one of her doctors noticed an irregular heart beat and suggested a pace maker. "But my heart has always been like that, dear," she told me on the phone. My brother was convinced by the physician, and gave his permission. She never recovered from the second operation, and after she was moved to a hospice, a nurse told me that her heart continued to beat irregularly. Until it stopped.

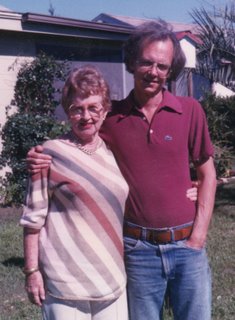

I don't know much about mothers, having had only one. She was named Alyce Anita by her parents but changed it to Peggy because she liked it better. And she thought it suited her red hair, which in later years she assiduously dyed. For most of my life, we were not close, either emotionally or geographically. She loved to gossip, read only Readers Digest condensed books, and knew nothing of music, art or literature. She was born in Winnipeg, Canada, but had absorbed all the prejudices of the South from six years of living in North Carolina and Georgia.

I went to high school in California, and we lived in a lily white suburb of Los Angeles. One day a friend I'd met in the high school band came to my house to visit. He was black. My mother, after slamming in the door in his face, went into the bedroom, shut the door loudly, and shouted: "I'm not leaving until he goes away." I was mortified.

I went to high school in California, and we lived in a lily white suburb of Los Angeles. One day a friend I'd met in the high school band came to my house to visit. He was black. My mother, after slamming in the door in his face, went into the bedroom, shut the door loudly, and shouted: "I'm not leaving until he goes away." I was mortified.My father was tall and silent, my mother was short and fussy. They hardly ever argued, but when they did it was usually my mother who would scream hysterical accusations at my father from the sanctuary of her bedroom.

When I brought my first wife home to meet her, my mother stood outside the guest bedroom at 6 in the morning and loudly complained about the sin of oversleeping. She herself would rise at dawn and scrub the kitchen floor.

After we settled on separate coasts, I would call my parents regularly and dutifully. They, on the other hand, rarely called me. I excused this, thinking it was from a concern not to meddle in our affairs. But my mother was an experienced and accomplished meddler, so it must have been my father's calming influence.

My father died slowly, of emphysema and congestive heart failure, and she was a loving and devoted nurse. After he was gone, she seemed to flourish in her new-found singularity. She took more of an interest in my families and pride in my accomplishments. After my second marriage ended, I began visiting her more often. We enjoyed shopping together, reading the National Inquirer and laughing at the stories, and we watched her favorite TV shows. She had an impressive grasp of the lives of celebrities.

As her body aged and shrunk, I noticed the courage with which she approached every new challenge. Giving up her driver's license after an accident that was her fault, she talked about the wonderful door-to-door bus service for seniors in her town. She was always cheerful, even while sending me to the store on an emergency errand to buy adult diapers. Optimism for Mom was a way of life and I came to respect the person she had become.

"My mother didn't know how to be a mother," she once confessed to me. Her mother had been cold and distant, and she was sent to a convent boarding school in Toronto at an early age. Hearing this, I began to see why my mother seemed flighty and superficial rather than warmly affectionate and loving. She had never learned how. And I, too, have struggled with being real, honest and loving.

Wherever we lived while I was growing up, she would attend the most socially acceptable Protestant church, accompanied by me and my brother. My father claimed to worship God on the golf course. After his death, I bought her a rosary and on my visits to Florida we would go to mass at the nearby Catholic church. She took great pleasure in receiving the Eucharist. I give her credit now for starting me on the spiritual path.

Slowly I let go of my judgements about her. I remembered how she had cared for me when I developed asthma at the age of six. She was there, patting my back, when I stood bent over, struggling for each breath. And when I broke my femur in a car accident after high school graduation and was forced to lie in bed for two months in a body cast, she changed my bed pan. After my second divorce, she defended me so vehemently against the woman who had rejected me that I had to take my ex-wife's side and urge a little compassion.

I am glad that I got to know you, Mom, before you died. And on this Mother's Day, I remember you with all the warmth, love and affection that you deserve.

No comments:

Post a Comment