At the end of the story there is a list of questions, and a vocabulary of words and expressions. The one that puzzled me was "mosquita muerta." I couldn´t figure out what a dead mosquito had to do with anything. In the story, the man, after he stops being nice to the girl, asks her to tell him her name. She says she doesn't remember it. Then he calls her "mosquita muerta."

It was a puzzle. Last night, in the tiny kitchen of Ofelia's apartment, I sat down at 10 PM (everyone eats late in Argentina) to a huge dinner of salad, rolls, soup, roast chicken, carrots, potatoes (both sweet and regular) and vino, enough to feed a futbol team. I suspect she thinks all students (despite my obvious girth) are starving. Stuffing it all in (it was the only polite thing to do) was complicated by the fact that after school

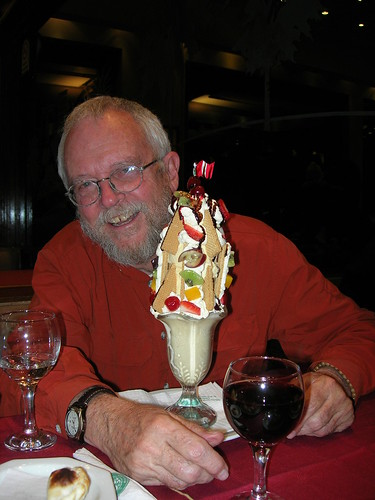

I went to our favorite cafe with Lorraine and Toni and I ordered a Copa Mundo for the outrageous price of 19 pesos (about $6.25), a monstrously huge ice cream sundae with fruit and some kind of liquor. It was over a foot tall. So I came home, after my usual nightly round on the internet at a neighborhood locutorio (surrounded by kids playing gigs and giggling over chat room chatter), to a conversation in Spanish with Ofelia and Rita.

I went to our favorite cafe with Lorraine and Toni and I ordered a Copa Mundo for the outrageous price of 19 pesos (about $6.25), a monstrously huge ice cream sundae with fruit and some kind of liquor. It was over a foot tall. So I came home, after my usual nightly round on the internet at a neighborhood locutorio (surrounded by kids playing gigs and giggling over chat room chatter), to a conversation in Spanish with Ofelia and Rita.Rita is Ofelia's tenant, probably in her forties, and I think of her as the Argentina Sophie Tucker. When she comes into the kitchen through the narrow door that connects with her room, I have to step aside from the table to let her pass. She is the Hardy to Ofelia's tiny Laurel. Her hair is dyed deep red and she waves hands featuring bright red fingernails when she talks. Rita warms up some coffee and tells Ofelia about her day which seems to involve three men. I understand about every tenth word, her sentences racing by like a formula one race car. "Su novio," I inquire innocently, wondering if she's talking about a boy friend. She roars with laughter and waves my question away.

To include myself in the conversation, I tell them about the story I am trying to understand. And I ask them the meaning of "mosquita muerta," the dead mosquito. Both laugh hysterically, in an Argentinean sort of way, with much shrugging of the shoulders and high pitched squeals. They proceed to tell me, by means of simple words and pantomime, that a "mosquita muerta" is a bad woman who pretends to be good, who acts coy and innocent but really is a slut at heart. Suddenly I comprehended at least one point of the story. The man mistook amnesia for a pose, and therefore she was ripe for seduction. He turned the victim into a victimizer, perhaps a prostitute looking for money. But what will stick with me forever is the way these two women acted out the meaning of the lunfardo expression, a description of the particular slang of porteños. In lunfardo, for example, che means hey, a boliche is a night club or disco, a pucho is a cigarette and a pendejo is an idiot. Now I could add mosquita muerta to the list.

Talking with Ofelia, and occasionally Rita, over dinner and breakfast is perhaps the best form of Spanish instruction I´ve had during my stay in Buenos Aires. It is very intense and sometimes wears me out. We´ve settled into a steady routine. I wake up at 7, shower and dress before planning the day and reviewing homework. Then at 8:30 I go into the kitchen where Ofelia has been preparing my toast; she cuts off the crusts after noticing that I didn't eat them. She boils my instant coffee with milk while I butter the six pieces of hard toast and cover them with marmalade. All the while we talk about the weather (it will rain in the evening, she said this morning before I left, but it's already started), and the construction noise in the street and in the building next door which is being renovated.

This morning, as I crunched the dry stale toast, we spoke of the apartment that she'd inherited from her mother 38 years ago, and of the price of real estate here and in the states. She said norteamericanos were buying luxury condos in the high-rise buildings in Belgrano and that property in Patagonia was being purchased also by foreigners. Shifting the subject, she says her mother was religious but not her father. Ofelia speaks in a squeaky voice and rarely slows down to help me comprehend. I tell her I don't understand her, and she tries again from a different perspective, sometimes pointing or pantomiming or using objects on the table to help this poor feeble norteamericano make sense of her linguistic reality.

It's not easy being a student of another language at a time when you should be rocking on a porch and reading detective novels. I recall my class in Oaxaca and remember how the 18-year-olds would go out drinking every night and STILL be able to speak and understand Spanish better than me in the morning. Here the students are a broader range in age (I'm still the top end), and the older ones go tango dancing rather than bar hopping, but I still struggle to make some progress. Smita, the 16-year-old, with a porteño's proficiency in the language, is scarey. A couple of the students are native speakers but wanted to learn grammar. Gradually some are falling by the wayside, their priorities changed. Amelia only came to school the first week, Ryan stopped attending classes last week, Toni may stop today. Several are going to Colonia in Uruguay today, believing that the experience of travel is more important than class. One of the students went back home after having a nervous breakdown. I doubt that it had anything to do with the difficulties of learning Spanish.

Eugenia is a marvelous teacher, animated, intelligent (she likes Noam Chomsky and we talked about Virginia Sapir and Benjamin Whorf yesterday), and she tailors her lessons to our individual problems. This week we're working on the subjunctive tense which is quite common in Spanish and hardly noticeable in English. Spanish makes a distinction between probabilities and certainties that no doubt accounts for the reason that magical realism is a popular form of literature and cinema in Latin America. It's hard to confuse the imaginary and the definite when you express each in a different tense. I get the principle, but I'm still a little weak on verb conjugations. I'm fearful of the final exam on Thursday for I know I shall certainly confuse verb stem endings in the different past tenses and subjunctive that we have been studying.

But in the end, no me importa. I am here to learn and understand and experience the reality and the possibilities of Argentina and Chile, and I have accomplished much of that in only three weeks. What grade I get (if I don't choose the pass/fail option) is unimportant.

No comments:

Post a Comment